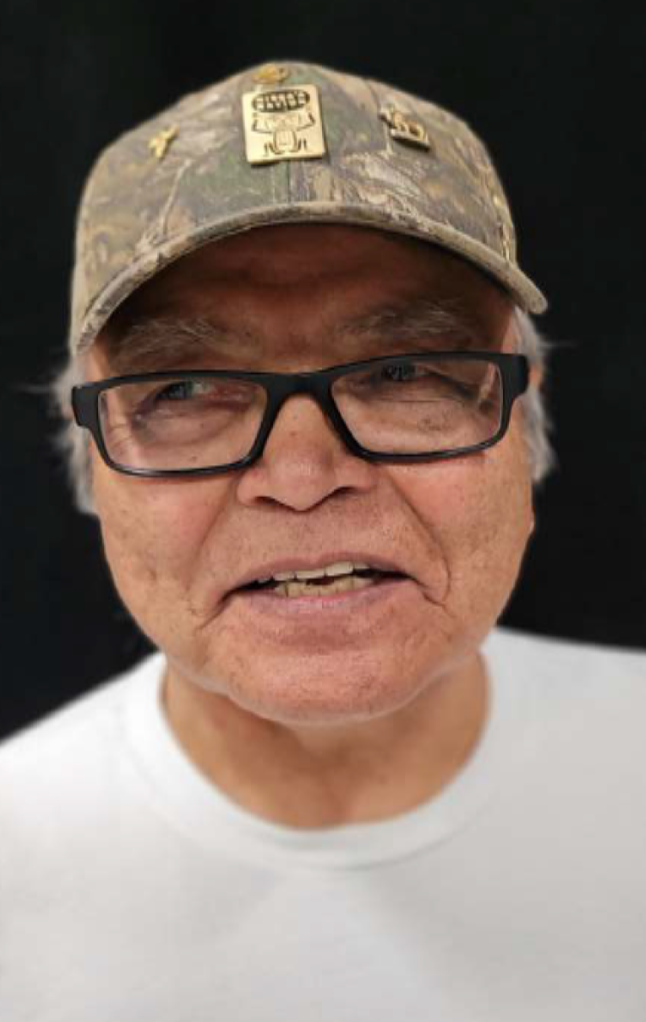

Mandy Nahanee /Shamantsut (Rise Above) / Lady Sinncere Skwxwu7mesh (Squamish) and Nisga’a

If we were in this reconciled place, it would be a place where nobody was poor, nobody was starving, nobody was without a home.

Mandy Nahanee

Mandy’s father went to St. Paul’s Indian day school, as did four of his siblings. His other four siblings went to full-time residential school and he did not get to know them until they finally came home. The day school in North Vancouver was a violent place and Mandy is still waiting for family members to feel like they can share what happened there.

Her mother grew up and went to day school in the Nass Valley. She said she didn’t experience any negativity, or any bad things. It was a positive experience for her. This was because when children had begun coming back hurt from residential school, the Nisga’a people there started working with the church and the Salvation Army, agreeing to have the children attend day school and learn that way of life, so that they would not be taken away and abused.

Mandy’s father and mother worked hard to make sure their children grew up with their culture, knowing who they were and where they came from.

“We didn’t grow up with the language. We had to work hard to learn our language,” Mandy says.

As for truth and reconciliation, Mandy says this: “If everybody did their part, we would not have murdered and missing Indigenous women, we would not have our children taken away by the ministry of child and family services. There’s tons and tons of First Nations that can really use donations. The Vancouver School Board and Vancouver school trustees donated an old school to Squamish Nation.

“This building is going to house our Squamish language baby program, for ages up to four years old. That is one, true active reconciliation, a permanent place for our babies to go to learn the culture, who they are, where they come from, give the foundation of who they are and give that really good start that they deserve.

“This misconception of Indigenous Peoples is if we get our land back, we’re going to kick people out. That’s not how Native people are. We’re giving, we’re caring. We don’t want anyone to suffer, we don’t want anybody homeless, we don’t want anybody poor. It’s just what we do, we take care of each other. So I think if we were in this reconciled place, it would be a place where nobody was poor, nobody was starving, nobody was without a home. Everybody would have a place, and a duty and a responsibility to upkeep and uphold each other with respect and dignity and integrity.”